PLACES AND LANDMARKS

Astoria’s Flatiron Building

Ilana Teitel

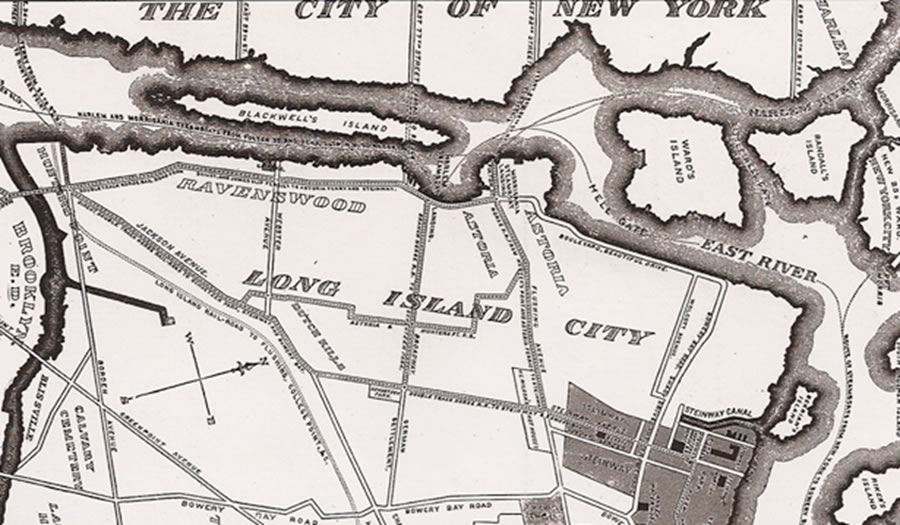

From colonial times through the early nineteenth century, most of Astoria’s activity and commerce was centered near the waterfront. However, during the 1840s and 1850s the neighborhood began slowly expanding inland. from the ferry landing at Astoria Boulevard. As the community grew, new roads were built, such as Astoria Boulevard, which runs east to Flushing, and Vernon Boulevard, which runs south to Brooklyn.

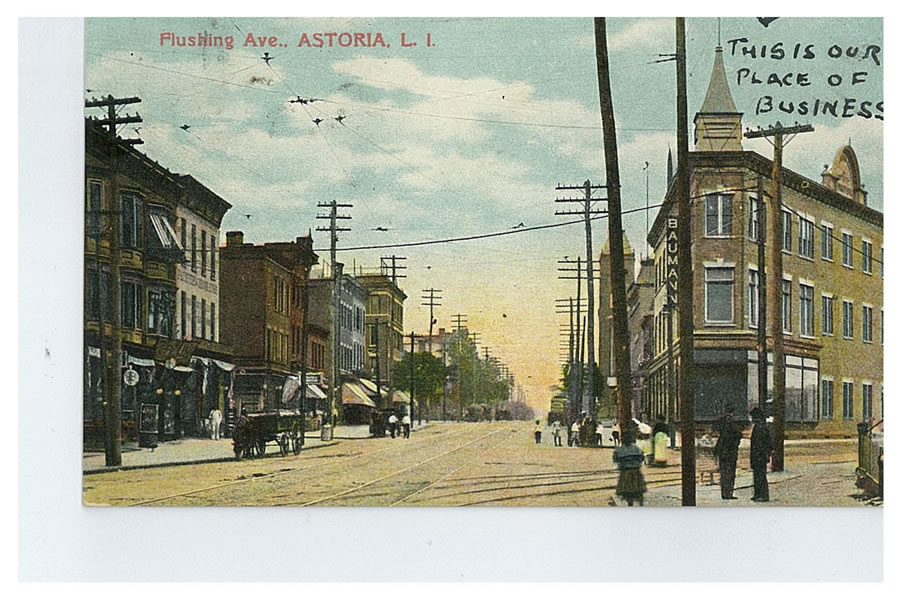

Astoria’s Flatiron Building stands at the corner of Astoria Boulevard and 27th Avenue and for decades has served as an unofficial landmark and gateway to the neighborhood. It stands four stories tall, with commercial spaces on the ground floor and residential units above. For decades, it was the home of the Gally Furniture store. Early twentieth century photographs and postcards show the store festooned with striped awnings and signs advertising furniture and ranges. The streets outside were bustling with horse-drawn carriages and trolley cars. In more recent times, elected officials and civic groups have supported efforts to repaint the building and restore it to its former glory. Luckily, the building’s current owner has more than met expectations by totally renovating its exterior to the wonderful conditions we find today.

Sources:

Burrows, Edwin G and Wallace, Mike. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Henely Rebecca. “‘Flatiron of Astoria’ Gets New Coat of Paint, Times Ledger, January 2012.

Illustrations Volume 3, Queens Library Archive.

Jackson, Kenneth T. The Encyclopedia of New York City.

New York: Yale University Press, 1995.

Eagle Electric Factory

Bill Peloquin

In 1920, brothers Louis and Philip Ludwig founded the Eagle Electric Manufacturing Company. The business specialized in producing electrical devices, switches, and circuit units and had three factories located throughout Queens. One of those factories was located on the corner of 19th Street and 24th Avenue, opposite Astoria Park. A photo of the old Eagle Electric factory can be seen below.

By the early 1980s, Eagle Electric began moving their factories out of New York, initially to other states, and then later to other countries including Mexico and China. The old 19th Street factory was sold to Cooper Industries, another electrical products manufacturer, in 2000.

In 2006, the Pistilli Realty Group purchased the factory and spent $30 million to convert it into a residential complex called Pistilli Riverview East. This once industrial site has been transformed from 125,000-square-feet of raw commercial space into approximately 350,000-square-feet of modern duplex lofts, duplex mezzanines, and both traditional and penthouse apartments. Many units have terraces and balconies, and residents enjoy private amenities such as a fitness center, laundry facilities, private reading and relaxation quarters, and parking.

Sources:

https://www.qgazette.com/news/2006-09-27/front_page/001.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eagle_Electric

https://forgotten-ny.com/2014/12/astoria-2014-part-2/

http://boromag.com/the-eagle-flew-the-co-op-the-eagle-electric-building-in-astoria/

First Reformed Church of Astoria (12th Street)

Bill Peloquin

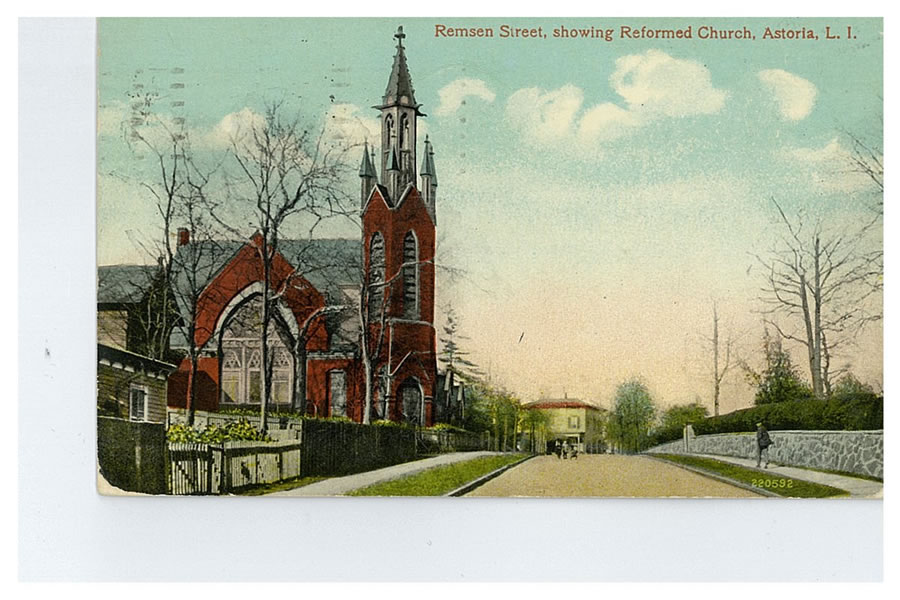

On the western side of 12th Street stands a 180-year-old church that has watched Astoria grow and change since its earliest days. In fact, the First Reformed Church of Astoria was built four years before the village was even named Astoria! It opened its doors the same year that Stephen Halsey, the “Father of Astoria,” arrived on the scene. The following is a brief account of the church’s intriguing history.

It all began with a small group of Christians—mostly Dutch Reformed and Presbyterians—that met at the Hallets Cove Schoolhouse on October 12,1835. At that meeting it was decided to raise money and build a church. Over the course of a year, they fundraised and even secured a significant contribution of $1,500 from the Collegiate Dutch Reformed Church of New York. Finally, workers laid the cornerstone of the new church on October 6,1836.

Though the group had been holding services long before the church was built, the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church didn’t officially recognize them until July of 1839. At a 2:00 p.m. service, John Bussing was ordained as the first deacon of the First Reformed Church of Astoria. Still, the church was without a fulltime pastor until August of 1840, when Reverend Alexander Hamilton Bishop was appointed the church’s first pastor.

The organ was installed in 1858 and incredibly it is still in use today. Luckily, the organ, along with the pews, pulpit furniture, clock, and bell were spared when a fire broke out in the church on November 28, 1880. The congregation subsequently decided to demolish the damaged church and construct a new building in its place. The cornerstone of the new church was laid on October 6, 1888, exactly fifty-two years after the original cornerstone was set.

Since the 1880 fire, the church has survived over the course of 135 years through decades of change and development in the area. It is one of the few places in the neighborhood where a person can still catch a glimpse of nineteenth century Astoria and experience the history of this great city.

The church’s current pastor, Rev. Dwayne Jackson, serves as the Clergy Liaison for the local police command. His work involves mediation between members of the community and helping them to build a peaceful relationship that will benefit both the local citizens and the patrol officers, where mutual respect is fostered.

Hallets Cove

Ilana Teitel

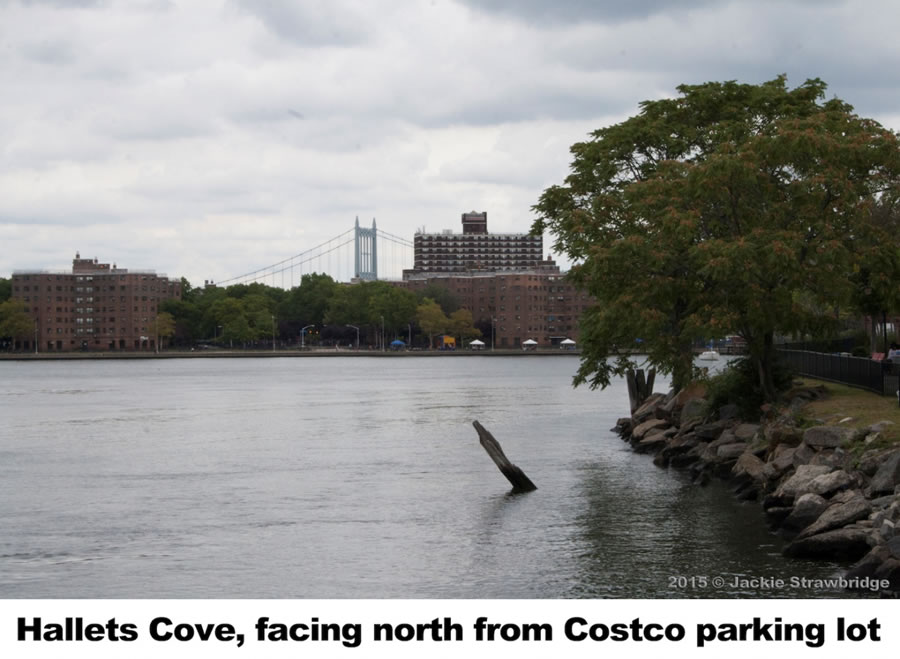

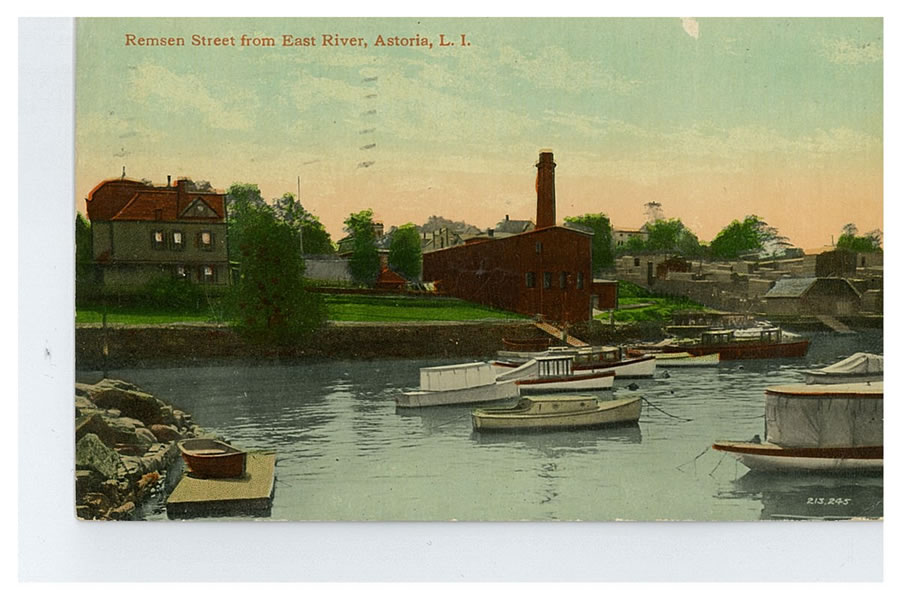

Hallets Cove has been used as a landing place for boats ferrying passengers, produce, and cargo since at least the days of Astoria’s first colonial settlements. It is named for William Hallett, who received a land grant from New Amsterdam Governor Peter Stuyvesant and was one of the first Europeans to live in present-day Astoria.

Both commercial and recreational uses persisted in Hallets Cove through the first half of the twentieth century. The Sohmer Piano Factory opened on Vernon Boulevard and 31st Avenue in 1887. Burns Brother’s Coal Company had a plant and docks on the Cove, and offices nearby on Vernon Boulevard and Welling Court. But a 1940s-era photo of a “swimming party at Brown’s Point (1st Street)” shows swimmers jumping into the water from the docks of waterfront houses lining Hallets Point.

A radio tower for WLIB was erected on the Hallets Cove Pier in 1953. Advertisements for the station touted the fact that it had “more Negro listeners in AM than any other N.Y. station” and reached “700,000 English speaking Jewish families.” During its installation, part of the 212-foot tower fell across Vernon Boulevard, injuring five people and narrowly missing the nearby playground. By 1967, WLIB relocated its tower to New Jersey, and the vacant pier began to deteriorate.

In recent years, as neighborhood residents have once again become more connected to their waterfront, a number of proposals have sought to revitalize Hallets Cove. The Long Island City Community Boathouse operates a free walk-up paddling program from Socrates Sculpture Park’s beach on the southern edge of the cove. In 2011, after soliciting feedback from the community at a series of public meetings, Green Shores NYC and the Trust for Public Land released a “Waterfront Vision Plan” for Astoria and Long Island City. One of the plan’s proposals was to “transfer the City-owned pier in Hallets Cove to the New York City Parks Department and renovate it to provide spaces for relaxing, fishing, enjoying the view, boat storage, and boat launch access. GSNYC later worked with the Waterfront Alliance on a more detailed conceptual plan for Hallets Cove, using the Alliance’s “Design the Edge” guidelines. That plan, designed by Star Whitehouse Architects, called for transforming the site into “a vibrant and ecologically resilient space” with native plants, a floating dock, and kayak storage. Councilman Costa Constantinides announced his support for this floating “eco dock” during his 2015 State of the District address, saying that the Astoria waterfront was once “a part of everyone’s lives in a real, tangible manner, for recreation as well as for business or transport.”

New Astoria Ferry Service

Ilana Teitel

Constantinides, Costa. Press Release: State of the District address. January, 2015.

Green Shores NYC. Astoria-Long Island City Waterfront Vision Plan. http://www.greenshoresnyc.org/waterfront-vision-plan.html

Jackson, Kenneth T. The Encyclopedia of New York City. New York: Yale University Press, 1995.

Jaker, Bill; Sulek, Frank; and Kanze, Peter. The Airwaves of New York. McFarland & Company, 1998.

Joseph Sandor Photographs, Queens Library Archives. “Mount Bonaparte Rediscovered.” Long Island Star Journal, August 1962.

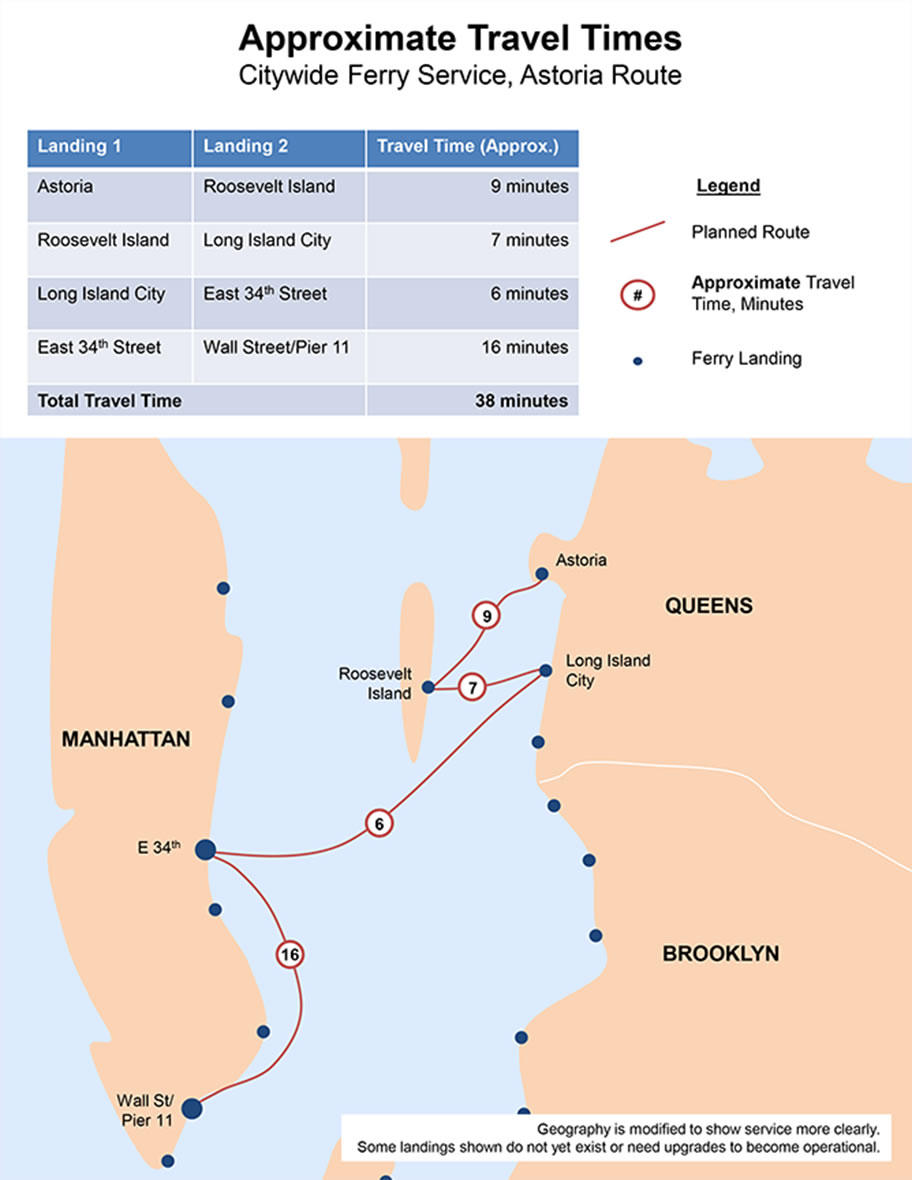

New York City Economic Development Corporation. Citywide Ferry Service. https://www.nycedc.com/project/citywide-ferry-service

Starr Whitehouse. Design The Edge: Hallets Cove. http://www.starrwhitehouse.com/waterfronts/design-edge-hallets-cove/

Waterfront Alliance. Hallets Cove Redevelopment. legacy.waterfrontalliance.org/halletscove

Hallets Peninsula

Bill Peloquin and Ilana Teitel

First settled by William Hallett in the mid-seventeenth century, Hallets Peninsula slowly grew from a farmstead into a bustling village. Homes and businesses grew up around the ferry and industrial sites lined the shore.

Hallets Peninsula, nestled between Hallets Cove and Pot Cove, was once a hub of activity in Old Astoria Village. William Hallett and his descendants farmed the area beginning in the 1600s. When Stephen Halsey began running ferry service and modernizing the town in the 1840s, the pace of development quickened. The streets leading to the ferry were filled with horse-drawn carriages and trolleys. Taverns and shops served locals and travelers from Manhattan. Grand estates lined the shoreline and more modest homes were built further inland. Astoria’s first high school was located on the peninsula.

Many of the old mansions were eventually replaced by industrial sites. When ferry service ended in the 1930s, businesses closed and the peninsula became more isolated. Astoria Houses brought thousands of residents to the area, but Hallets Peninsula has continued to suffer from a lack of transportation, schools, and retail.

Today, two planned developments, and the imminent return of ferry service, promise to help revitalize Hallets Peninsula. New homes, schools, shops, and community facilities might make the area the center of Astoria once again.

Astoria Houses

Bill Peloquin

The Astoria Houses were built in 1948 in an effort by the City to create affordable housing for low- and middle-income families. The development accounts for roughly half of the Hallets Peninsula. There are 22 seven-story buildings in total, which contain 1,102 apartments that house roughly 3,135 people. The Astoria Houses are run by the New York City Housing Authority. The complex sits on 30 acres bordered by 27th Avenue, 8th Street, Hallets Cove, and the East River.

http://qnsmade.co/history/astoria-houses/

https://www.nytimes.com/1992/07/05/nyregion/worlds-apart-in-queens.html?pagewanted=all

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/gsc1994000040/PP/

http://www.nyc.gov/html/nycha/html/developments/queensastoria.shtml

Hallets Point Development

Ilana Teitel

The Durst Organization broke ground on its Hallets Point development in January of 2016 Hallets Point will transform the now isolated stretch of the Queens waterfront into a thriving residential community with a supermarket, a vibrant mix of retail stores, an extended and enhanced esplanade, parklands, and renovated playgrounds.. Hallets Point is a 2.4 million-square-foot project that will transform the Astoria waterfront with approximately 2,400 rental residences across sever buildings, 20% of which are affordable apartments, as well as a The project also includes community facilities, a site for the construction of a new K-8 public school, and an additional development lot for the New York City Housing Authority. The first building on the campus, with 405 residential units and a supermarket, is scheduled to open in 2018. It will be one of the few large residential developments in New York City to be completely off the electrical grid, generating power and heat through three natural gas “co-generating” plants.

(Editor’s note: As of February 2016, the Durst Organization has put plans for most of the development on hold. Because N.Y. State has not renewed the 421-a tax abatement program, they’re unable to obtain the necessary financing. Follow OANA to receive updates on this.)

Astoria Cove Development

Ilana Teitel

Astoria Cove is a 2.2 million-square-foot project being planned by Alma Realty for the northern end of the peninsula, which will bring in another 1,700 residential units to the neighborhood. The development will be the first project built under the City’s new mandatory inclusionary zoning program and 460 (about 27%) of its units will be designated as affordable housing. The project will also include upgrades to local parks, a supermarket, and space for a new public school. The developer has also promised to pay fair wages to construction workers building the project.

Jay Valgora, Astoria Cove’s architect, touted the benefits of revitalizing the area: “we believe that the waterfront is the single greatest opportunity for New York City and cities throughout America. We can’t build another Central Park; the next Central Park is the East River.”

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PSM_V28_D451_Hell_gate_new_york.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PSM_V10_D115_Hell_gate_plans_for_demolition.jpg

https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/whitey-ford-field/history

http://www.nyc.gov/html/nycha/html/developments/queensastoria.shtml

https://www.dnainfo.com/new-york/20150121/astoria/hallets-point-project-break-ground-october

https://therealdeal.com/2016/01/14/dursts-hallets-point-to-generate-own-electricity-on-site/

http://www.capitalnewyork.com/article/city-hall/2016/01/8587998/hallets-point-dursts-take-their-next-big-development-grid?news-image

https://therealdeal.com/new-research/topics/property/astoria-cove/

https://www.durst.org/properties/

https://www.dnainfo.com/new-york/20160218/astoria/hallets-point-project-halted-day-after-mayor-attended-its-groundbreaking

SCHOOLS

Ilana Teitel

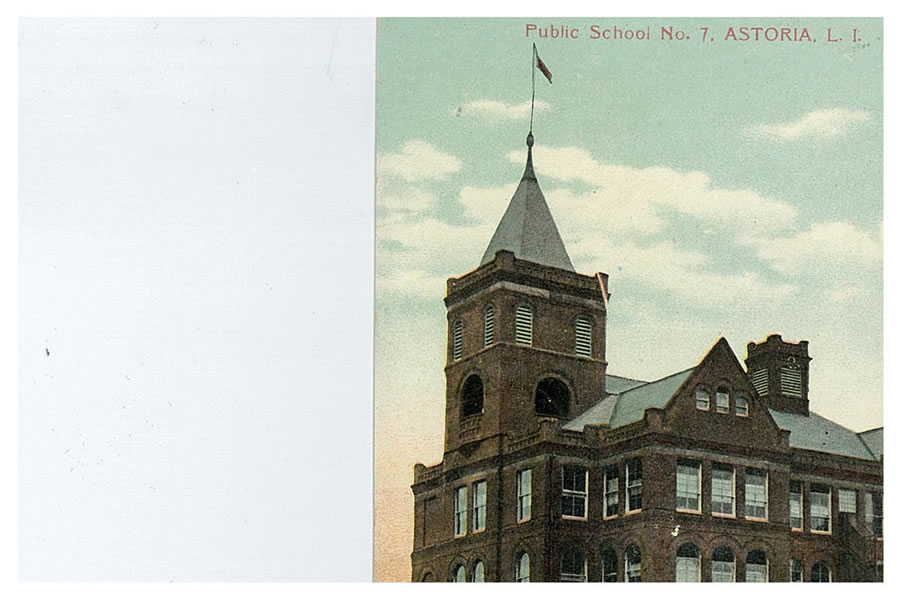

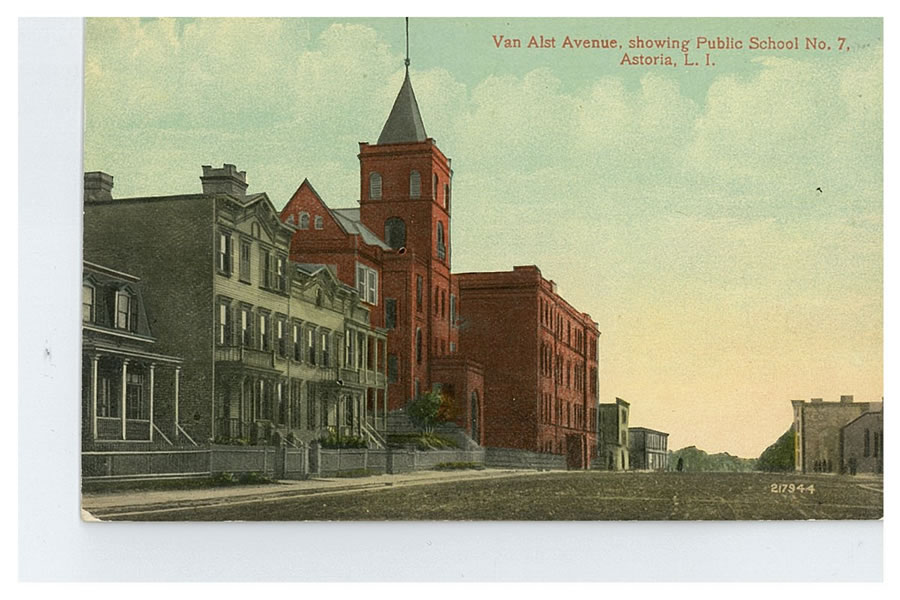

The new high school’s building had once been the home of Stephen Halsey, who incorporated the village of Astoria in 1839 and went on to lay out the neighborhood’s street grid, operate the ferry to Manhattan, and run the Astoria Gas Works. The mansion, on what is now 2nd Street between Astoria Boulevard and 27th Avenue, was constructed from stone quarried on the site. A century later, it was said to be “still rugged as a granite fortress.”

Halsey sold the house in 1870 to a “river man” named Captain Munson. When Munson died in 1893, the village bought the mansion for use as a school. The building was used as a high school only until 1905, when Long Island City High School opened near Queens Plaza, but it served as an elementary school, P.S. 9, until the 1940s. By that time, it was the oldest building in use as a New York City public school, and among the oldest in the nation. Teachers and parents bemoaned the fact that P.S. 9 lacked an auditorium, cafeteria, and gymnasium, and worried that plans for residential development would lead to overcrowding in the district. The building was finally razed to make way for the Astoria Houses development, and P.S. 9 was replaced with P.S. 171 on 14th Street between 29th and 30th Avenues.

In 1995, Long Island City High School moved back to Astoria, when a brand new building opened on Broadway and 14th Street. Architecturally, today’s LICHS is a far cry from Stephen Halsey’s granite mansion. It boasts an Olympic sized swimming pool, two gyms, a football field, and a professional kitchen for its Culinary Arts Program. But, like its 1893 antecedent, today’s LICHS serves a bustling, changing neighborhood with many immigrant families.

And things might soon be coming full circle for Astoria’s students. Two planned developments on Hallets Peninsula have set aside space for the New York City School Construction Authority. In the years to come, new modern school buildings might rise not far from Old Astoria Village’s original P.S. 9.

Burrows, Edwin G and Wallace, Mike. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Jackson, Kenneth T. The Encyclopedia of New York City. New York: Yale University Press, 1995.

Joseph Sandor Photographs, Queens Library Archives.

“Ox-Cart School Built in 1840 Still Used in Astoria.” Long Island Star Journal, November 1945.

New York City Department of Education. Long Island City High School.

New York City Department of Education. Long Island City High School. https://schools.nyc.gov/SchoolPortals/30/Q450/AboutUs/Overview/default.htm

Vertical Files, Queens Library Archives.

Mansions and Old Houses

Ilana Teitel

Just blocks from Astoria Park, a cluster of historic homes grace 12th and 14th Streets between 27th Avenue and Astoria Park South. Many similar homes on the same blocks have been torn down in recent years, and the remaining ones often look so out of place in the City that they startle passersby who come across them. But at the time they were built, they were actually not the grandest homes in Astoria.

In the 1840s, when much of upper Manhattan was still unbuilt, one could see the cliffs of the Palisades from high points in Astoria. Astoria had been home to a handful of small estates since Colonial times. In the nineteenth century, the waterfront views and bucolic countryside of Astoria and nearby Ravenswood attracted wealthy Manhattanites who built large estates, summer homes, yacht clubs, and docks along the shoreline.

The Rapleyea Mansion was built before the American Revolution at the intersection of Main Street and Astoria Boulevard. It later became the Red Tavern, and in 1903 had a basement tap room with Colonial-era fixtures, as well as an upstairs room that had been preserved as an old fashioned hostel room with bunks like those on a ship. Rumor has it that the Manhattan Cocktail was invented in that underground bar one day as farmers waited for the tide to turn and the Manhattan ferry to start running again.

The Strang House stood on the east side of Broadway and Vernon Boulevard, near today’s Socrates Sculpture Park. In 1903, a relative of Charles Strang recalled that the house was old when he bought it in 1823, and that it had pegged wooden construction and no nails.

The Stevens House, built by a Revolutionary War general, stood near Vernon Boulevard and 30th Road. The mansion’s lawns ran down to Hallets Cove, where the family moored boats they used to travel to work on Wall Street.

As a major residential development prepares to break ground at Pot Cove, historians are hopeful that an archeological dig might yield relics from the past. The Whittemore Mansion once stood on the site.

Colonel George Gibbs bought much of the land in Ravenswood in 1814. After his death in 1833, the land was divided into nine estates and by 1848 villas and mansions dotted the shore. A century before The Great Gatsby depicted the great estates of Long Island’s North Shore, the villas of Ravenswood were “the first iteration of the Gold Coast.”

By 1870, when Long Island City was incorporated, “aristocratic Ravenswood” and “affluent Astoria” joined with the more commercialized Hunters Point to form the fledgling city. But growing industrialization and the automobile eventually drove many of the aristocratic families out of Astoria, further east. Most of the mansions were divided into multi-family houses and torn down after World War II.

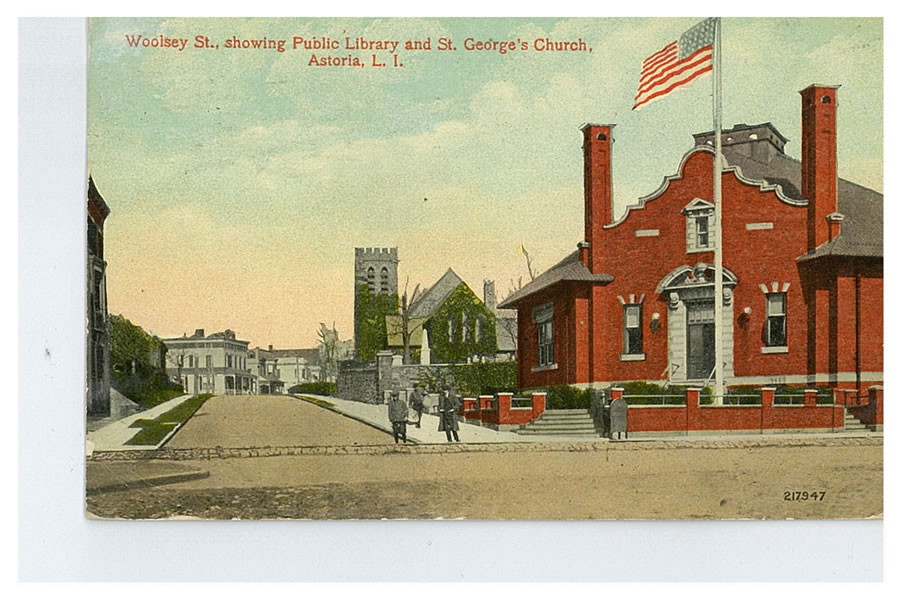

12th Street (once known as Woolsey Street) and 14th Street (once called Remsen Street) are a few of the blocks where many historic homes remain intact.

The Blackwell House, built by a member of the family that once owned Roosevelt Island and renowned for Elizabeth Blackwell, the nation’s first female physician, was built sometime between 1830 and 1850. It’s now the home of a church, the Greek Orthodox Cathedral of the Mother of God. Like many homes in the area it also features a tunnel that once ran down to the water’s edge.

These tunnels were used by servants to carry produce and other goods directly from docking ships without being seen by the wealthy owners above. Neighborhood legends have also suggested more intriguing uses for some of these tunnels. It’s long been suspected that some Astoria homeowners participated in the Underground Railroad, and that the tunnels were used to help escaped slaves make their way down to the river where boats were waiting to sail them to freedom. Old timers also say that during Prohibition, the tunnels were used to smuggle alcohol off of ships docked nearby.

The “Tara House”—reminiscent of the mansion in Gone with the Wind—was built in 1832. Once owned by Dr. Baylies, a local physician, it has seventeen rooms and nineteen fireplaces.

Sources:

Burrows, Edwin G and Wallace, Mike. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Jackson, Kenneth T. The Encyclopedia of New York City. New York: Yale University Press, 1995.

“Three Historical Homes in Astoria.” Long Island Weekly Star, January 1903.

“First Manhattan Mixed Here.” Long Island Weekly Star, December 1936.

“Mysterious Tunnel Marks Old House.” Long Island Press, April 1970.

“This Old House Looks Swell.” New York Daily News, February 1984.

“Who Lives There Anyway?” New York Times, August 1991.

Joseph Sandor Photographs, Queens Library Archives.

Vertical Files, Queens Library Archives.

Ravenswood

Bill Peloquin

In a similar origin story to that of Astoria and Hallets Peninsula, Ravenswood got its start when the Dutch granted Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island) and a strip of the Long Island coast to Captain Francis Fyn in 1651. After the English defeated the Dutch in 1666, ownership of the land passed from John Manning to Robert Blackwell to his relatives until it was acquired by George Gibbs in 1814. Gibbs planned to establish a private residential property but died in 1833 before he could complete the project.

Around this time, it is believed a local clergyman named Rev. Francis Hawks wanted to honor the Episcopal bishop of North Carolina, John Ravenscroft. Ravenscroft was not thrilled by the idea of his name being associated with a random town in Long Island, so Hawks tweaked it to Ravenswood. Somehow, the name stuck and has remained for more than 130 years!

In 1848, Gibbs’ land was sold to four separate developers, who built several mansions on the property. Ravenswood never became an independent village, unlike Astoria, because the population wasn’t large enough, nor was there a sufficient commercial presence in the area. It was simply a part of the town of Newtown until 1870, which is when a number of neighborhoods (including Astoria, Hunter’s Point, Sunnyside, and Steinway) were combined to form Long Island City.

Ravenswood began a drastic change in 1875, when the first commercial buildings were constructed. As a result, the majority of the existing mansions were converted into offices and boarding houses. By 1900, Ravenswood was almost entirely commercial. However, in 1951, construction was completed on the Ravenswood Houses, ensuring that the neighborhood would never entirely lose its residential roots.

Shore Towers

Bill Peloquin

Another residential high-rise not far from the incoming Hallets Point development made waves more than two decades ago. In 1990, construction was completed on the Shore Towers condominium building, located by Pot Cove and the southwest corner of Astoria Park.

With twenty-three floors, it was the tallest building along Astoria’s coast by a wide margin. Some local residents complained that the building blocked their view of the Manhattan skyline; the same concerns are now echoed by those who live near the Hallets Point site. Back in 1990, a writer for the New York Times provided a prescient prediction about the area’s waterfront property: “Will it all now go residential? Not overnight, certainly, but planners have long recognized that specific sites will lend themselves to midrise waterfront residential development in the long run.”

Piano Factory

Bill Peloquin

In 1872, German immigrants Hugo Sohmer and Joseph Kuder founded a piano manufacturing company called Sohmer & Co. Prior to starting the company, Sohmer had apprenticed as a piano builder at the Schuetze & Ludolff’s factory and spent two years studying piano making in Europe. Kuder had worked for a number of piano makers previously, including Steinway & Sons. Over the next decade, Sohmer & Co. would become a thriving business that expanded to multiple locations throughout Manhattan and Brooklyn.

In 1886, Sohmer & Co. built a factory in Astoria. The six-story brick building was designed by architectural firm Berger & Baylies and featured a clock tower at one corner. The building was extended south in 1906, with the addition attributed to architect Franklin Baylies. Sohmer & Co. manufactured its pianos in the factory until 1982, when it was acquired by keyboard company Pratt, Read & Co. As a result of the new ownership, the company moved its piano factories to Connecticut and the Astoria plant was taken over by the Adirondack Chair Company.

The Sohmer & Co. Piano Factory has long been regarded as a historic building and achieved landmark status with the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2007, following multiple hearings in the 1980s and 1990s. Not long after, developer Angelo Aquisto converted the building into residential housing. These days, the Piano Factory Apartments are some of the most sought-after living spaces in all of Astoria. And for those of us who can only afford to admire the building from the street, the restored clock tower will always give us the time of day.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sohmer_%26_Co.

http://www.nyc.gov/html/lpc/downloads/pdf/reports/Sohmer.pdf

https://queens.brownstoner.com/2014/03/queenswalk-astorias-sohmer-piano-factory/ https://streeteasy.com/building/the-piano-factory-31_01-vernon-boulevard-astoria

St. George’s Church

(Based upon information provided by St George Episcopal Church)

(Complied by Mr. Charles Egleston and Mr. James Olszewski)

Episcopal services in what is now Astoria began about 1800 in private homes and were conducted by clergy from St. James’ Church, Newtown (today called Elmhurst). One of those who offered their residence to be used as a space for worship was Mr. Samuel Blackwell. He would also generously donate towards the erection of the church that would become St. George’s. The first recorded mention of the church is found in the papers concerning the 1828 Diocesan Convention for the Episcopal Diocese of New York.

The church famously played a role in the naming of Astoria after John Jacob Astor donated $500 towards the parish’s rectory Female Seminary.

The parish was officially incorporated in the eyes of the state in 1835 and the Diocese of New York.

In 1870 the village of Astoria was absorbed into the newly formed Long Island City, and St. George’s Church has sometimes been referred to as “St. George’s Church, Long Island City”. The wood-frame church was destroyed by fire on January 10, 1894. From the time of the fire until August, the congregation worshipped in the Chapel of the Reformed Church.

During the summer, the rectory building was moved from its former location to the side of the church property fronting on Franklin Street, and the larger portion of it was remodeled into a Parish House, including a chapel and a Sunday School Room. The parish house, the much-modified Astoria Institute building, was fitted out as a worship space, and was used by the church until a new church could be built.

The present day church opened in 1904. It’s built out of stone that was blasted from the Queens Bank of the East River during the construction of the Ed Koch Queensborough Bridge.

The parish house was located at 14-22 27th Avenue until it was demolished circa 2005 and is now the site of the Gloria D’Amico Senior Residence.

Under current rector Rev. Karen’s Davis-Lawson’s leadership the congregation has experienced growth, including meditation on a topic selected by the Rev. Karen. Members of the congregation also engage in weekly Bible Study. Through Mother Karen’s encouragement, spirits are being renewed and the congregation has undertaken a Capital Campaign to restore the church building to further the parish’s longstanding ministry.

Sources:

http://www.astorialic.org/topics/worship_p.php

St. Rita’s Church

Ilana Teitel

St. Rita’s Parish was founded in 1895 as a Mission of St. Patrick’s Parish, in a garage on 9th Street.

The present church at 36-11 11th Street was opened in September 1900. The cost of the ground was $5,600 and the edifice cost $12,500. The church is 45 feet by 96 feet and has a seating capacity of 400.