OLD ASTORIA

Conquering Hell Gate

Ilana Teitel

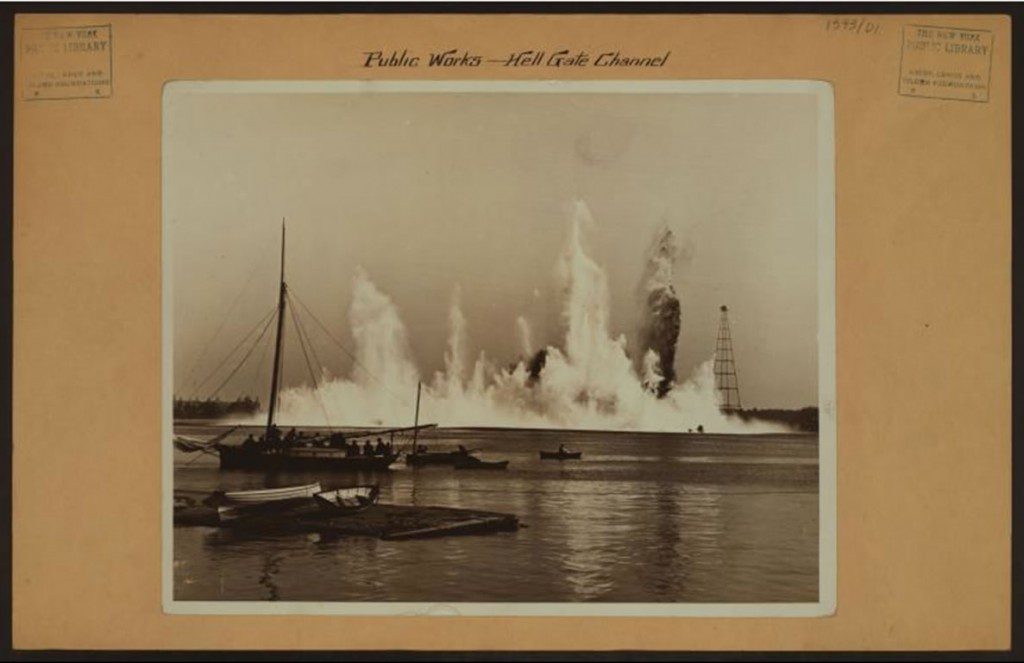

On October 10, 1885, 50,000 spectators lined the shores of the East River. A hundred of them came equipped with cameras—a staggering number for the day. They were there to witness and record the world’s largest controlled detonation. Mary Newton, the daughter of a local general, pressed a button that blasted nine acres of the river’s surface 150 feet into the air.

This was the Flood Rock explosion and it was the culmination of an enormous nine-year undertaking. The US Army Corps of Engineers had constructed a seventy-foot shaft, drilling and boring into underwater rocks. As a result of the blast, part of the treacherous Hell Gate passage became more navigable. Ships from New York City’s busy docks could now save time and fuel as they made their way out to the Atlantic. This huge feat of engineering marked just one of the times that Astoria has captured the public’s imagination.

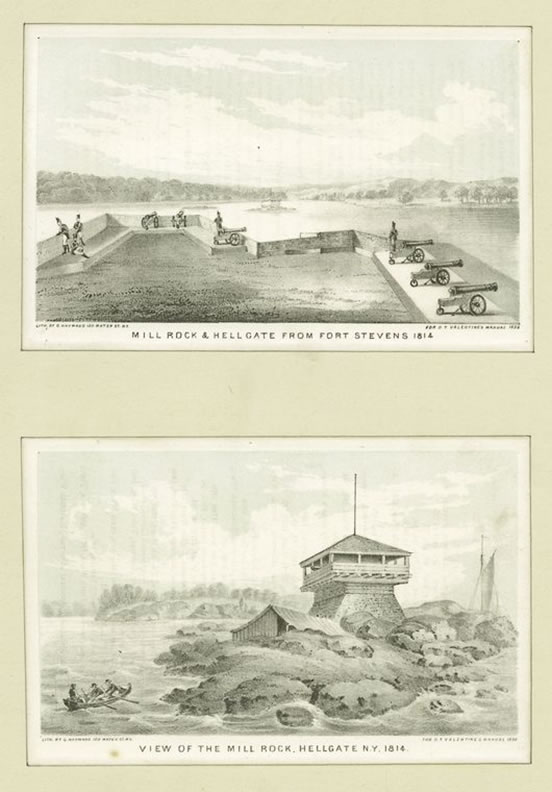

The swirling waters of Hell Gate had been notorious for centuries. “Hell Gate” is a corruption of the Dutch hellegat, meaning “passage to hell.” Sea captains from the seventeenth century on described the difficulty of navigating the tidal flows and gave colorful names to the passage’s swirling eddies and rocks. Washington Irving wrote about a fisherman guiding his skiff “from the Hen and Chickens to the Hog’s back, and from the Hog’s back to the Pot, and from the Pot to the Frying-pan.” Some of these names have been lost to history but the bubbling waters of “the Pot” live on in the name of Pot Cove, just south of Astoria Park. In the 1850s, when the New York Harbor Commission first appealed to the Federal government for help in clearing the rocks, an estimated 1,000 ships a year ran aground in the area.

Long before Europeans arrived, Native Americans were crossing the river from Manhattan. The land now known as Queens was scarcely populated, but its forests and wetlands were used as hunting grounds by the Mattinecock and Maspeth peoples, who may have been related to the Canarsie tribe in Southern Brooklyn and Staten Island. They called the area from present-day Long Island City to Corona “Wandownock” or “fine land between the two long streams,” referring to the East River and Flushing Bay.

The earliest European settlers reported a large midden—basically a dumping ground for oyster and clam shells—somewhere along the shore. There’s no consensus about exactly where this was, but an archaeological dig planned as part of an incoming development project at Pot Cove will attempt to find it.

Settlers, Colonists, and Revolutionaries

Jacques Benfyn, a member of the Dutch West India Company, was the first European to receive a land grant in present-day Queens. Benfyn hired workers to plant grain and construct buildings just north of what is now Costco and Socrates Sculpture Park. Six years later, fighting between the Dutch and local Native Americans intensified, causing Benfyn to abandon the settlement for the safety of Manhattan.

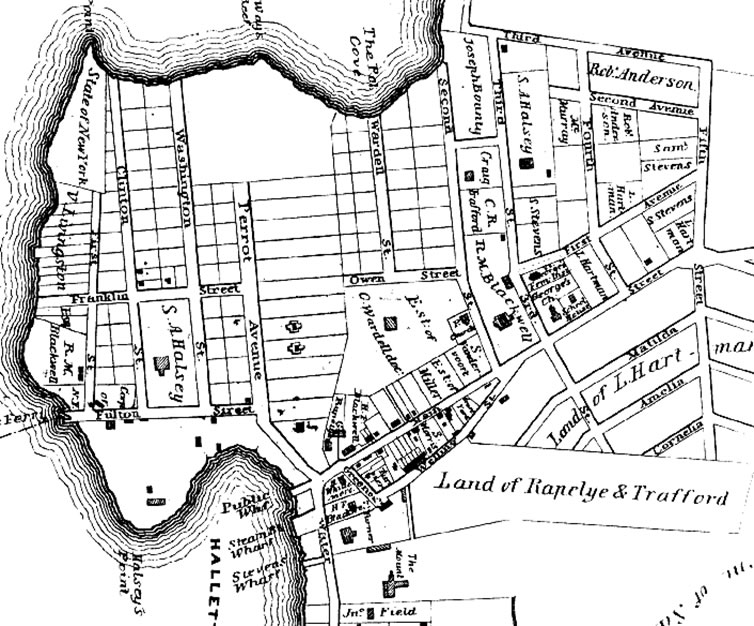

The abandoned plantation gained the attention of William Hallett, an Englishman living in Greenwich, CT. On December 1, 1652, Governor Peter Stuyvesant issued a deed declaring that he “hath granted and allowed unto William Hallett a Plot of Ground at Hellgate upon Long Island called Jarcks Farm.” This land, consisting of “woods and great swamp” was described as “beginning at a great rock that lays in the meadow and does upwards toward Cripple Bush.” Twelve years later, Hallett expanded his settlement with land “bargained and sold” by Shawwestcout and Erromahare, two members of the Shawkopshee people from Staten Island.

Over the next 100 years, Hallett and his descendants developed the area into a thriving farming community. Early settlers transported grains, livestock, timber, and firewood across the river from Hallets Cove to the growing city of New Amsterdam. The first commercial ferries began operating in the 1700s from Hallets Cove to Hornes Hook—present-day 86th street—in Manhattan. As time went on, pieces of Hallett’s original acreage were sold to various families and by 1800 only the land containing Old Astoria Village remained in the family.

Astoria played a part in the American Revolution as a staging ground for British Forces. 10,000 troops camped in the area after the Battle of Long Island, pillaging farms and stealing food. There was a British Battery at Hallets Cove. In 1780, the HMS Hussar, a British frigate carrying gold and silver for the British Army’s payroll, plus dozens of American prisoners of war, reportedly struck Pot Rock and sank in Hell Gate. The wreck was never found and rumors persisted that the sinking was staged by crew members who made off with the fortune.

After the Revolutionary War, Ebenezer Stevens, one of George Washington’s generals and a participant in the Boston Tea Party, bought part of the Hallets’ pear and cherry orchards. He built a mansion that he called “Mount Bonaparte” on what is now the east side of Vernon Boulevard and 30th Road. Stevens’ lawn sloped down to the cove, where he and his descendants moored boats that took them to work in downtown Manhattan and to fish nearby for blackfish and bass.

During the War of 1812, the military feared that the British Navy’s steamboats would make their way through Hell Gate and attack New York Harbor. General Stevens came out of retirement to command the newly constructed Fort Stevens (named in his honor) on Hallets Peninsula. A lighthouse remained at the site until 1982. Today it is a City park and baseball field named for Major League Baseball’s Whitey Ford, who grew up in Astoria.

The 1800s: Mansions and Industry

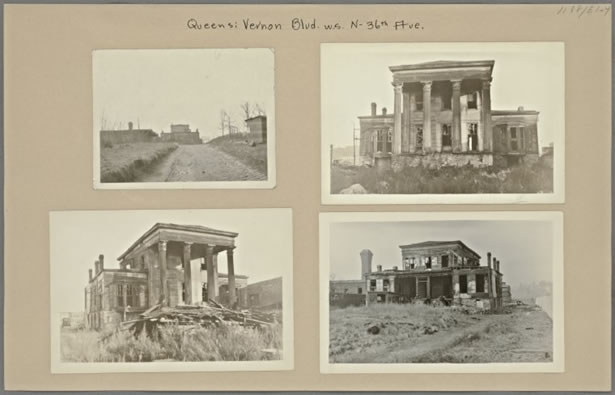

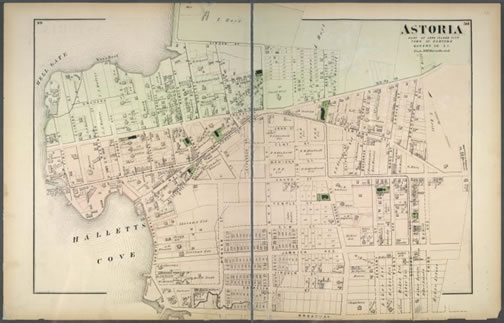

Two competing forces defined the Astoria waterfront throughout the nineteenth century. Wealthy New Yorkers built grand estates and stately summer homes along the shoreline. Meanwhile, factories, warehouses, and chemical plants on the Queens waterfront fueled the growth of a rapidly developing city and drove people away from enjoying time on the waterfront.

In the 1800s, the high ground in Astoria afforded views all the way to the cliffs of the Palisades in New Jersey. Affluent Manhattanites eager to escape the crowds, pollution, and diseases of the City, turned to rural Queens. Villas dotted the shore in Ravenswood and Old Astoria Village. These wealthy residents swam in the coves, sailed in local yacht clubs, fished in the river, and hunted ducks, plover, and snipe in the nearby marshes of Sunswick Creek (roughly along today’s 21st Street.) The New York Times urged New Yorkers to make the trek out to Queens. The Times extolled the pleasures of leisurely strolls along the waterfront, writing, “There are charming residences and delightful lawns at Ravenswood and Astoria. It is lamentable, that with such fine weather and pleasant country promenades at hand, our fair friends, especially of Brooklyn and Williamsburg, do not avail themselves of their privileges.”

Old Astoria Village would remain a quaint farming town until a wealthy fur trader named Stephen Halsey arrived in 1835 with big plans for development. He began to transform Old Astoria Village into a bustling town complete with new roads, houses, stores, churches, schools, and factories. He also bought and modernized the existing ferry service to Manhattan, moving it to Hallets Point at the foot of Astoria Boulevard.

By 1839, Halsey had decided that the area needed a new name. Halsey had connections to the biggest fur trader of the time, John Jacob Astor. He proposed that Astor donate $2,000 towards the construction of a new Episcopal female seminary in exchange for naming the village after him. Astor only offered $500, but the money was eagerly accepted and the village was officially named “Astoria,” much to the dismay of most residents who favored keeping “Hallets Cove” or calling the village “Sunswick,” a Native American name for a creek running along present-day 21st Street. The building that Astor funded eventually went on to become the rectory for St. George’s Church . In 1840, the New York Legislature officially incorporated the village under the name Astoria.

But by the 1860s, the bucolic mansions began giving way to industry. As New York City and Brooklyn adopted more stringent regulations, Queens—which was still made up of independent towns and villages with fewer rules and cheaper land—became an attractive site for industry. Distilleries, varnish factories, chemical works, and oil refineries sprung up along the waterfront.

Factories, farmland, and mansions all kept the Astoria waterfront busier than ever. Commuters travelled both ways, with ferries bringing wealthy bankers and lawyers from Astoria’s mansions to their downtown offices and then returning with immigrants who lived in Manhattan’s tenements and worked in Astoria’s factories. Dozens of docks served the area’s factories and plants, as raw materials and finished products were shipped in and out on barges.

Farmers on their way to sell their crops in Manhattan, workers at the Steinway Piano Factory and other new enterprises, and a growing number of residents traveled to and from the Astoria ferry on horse-drawn carriages, stagecoaches, and later, trolley cars. Travelers often stopped to shop or have a drink along the way and a growing number of inns, stores, and taverns opened up to cater to them. Astoria Square, bounded by the present-day intersections of 21st Street with Astoria Boulevard, 27th Avenue, and Newtown Avenue, grew into a busy junction and the unofficial entrance to Astoria Village. An 1885 photograph shows Moritz Albert’s Saloon at the corner of Astoria Boulevard and Newtown Avenue. A sign in German advertised wine and beer. The Red Tavern, housed in an old colonial mansion, was another popular watering hole. When the “old Astoria Hotel” on Hallets Point was demolished in 1939, Astoria old timers recalled that it had once been “a resort out in the sticks” known at various times as Corey’s Hotel, Kenney’s Inn, and Christy Arnold’s. The Manhattan Cocktail was said to have been invented at the Red Tavern, a nearby bar in an old colonial home, as people endured an especially long wait for the tides to turn and the ferry to resume running again.

THE 1900S: GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

This movement of people and goods across the river gave rise to both the Flood Rock detonations and the twentieth century’s frenzy of bridge construction.

.

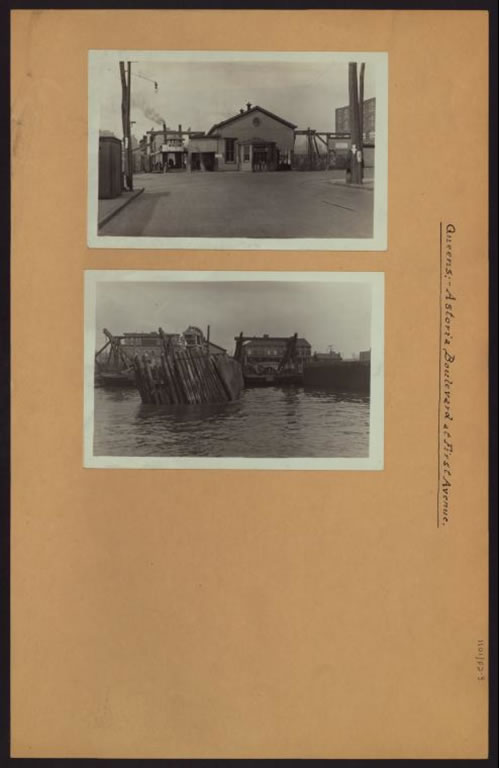

People and goods were moving between Queens and Manhattan in increasing numbers. But by the middle of the 1900s they often travelled on cars and trucks and trains instead of by boat. After the Hell Gate Bridge and the Triborough Bridge were built, ferries stopped running between Astoria and Manhattan.

.

The early 1900s also saw the creation of Astoria Park and Rainey Park, giving all local residents access to the waterfront on land once occupied by a few huge estates. Swimming and boating were still popular pastimes.

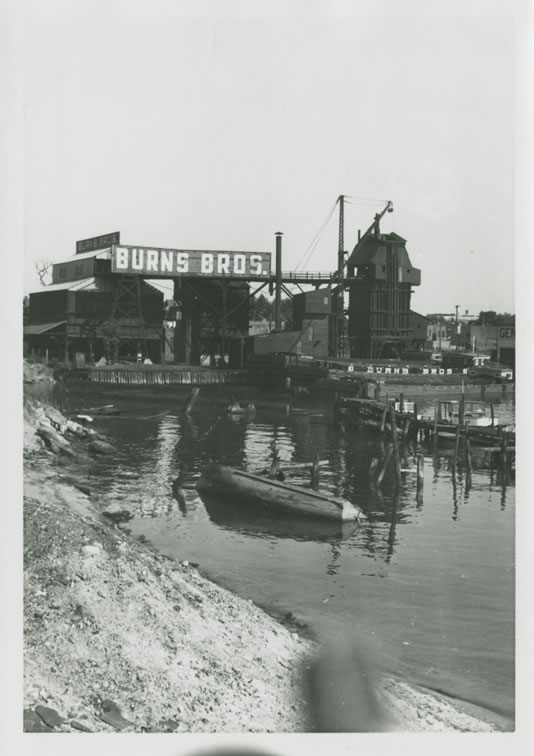

Industry in Astoria grew as well, with factories, gas tanks, and coal plats lining the shore from Ravenswood through Pot Cove. Astoria continued to supply the materials for building New York City. Where colonial settlers once cut down forests and shipped timber to Manhattan, in the 1930s, one of Vernon Boulevard’s stone yards proclaimed itself the “marble headquarters of the world” and the Mary E Burke barge ferried bricks across the river from Ravenswood.

Astoria continued to capture people’s imagination. Decades before the Lonely Planet guide named Queens as a top travel destination, intrepid reporters were touring Queens, and coming back with conflicting reports. In 1931, Robert Littel, a columnist at the New York World, wrote an unfavorable review of Astoria. Queens residents have always been proud of their neighborhood. Little received a barrage of angry letters after he called the neighborhood a place “where natural beauties and the grandeur of desolation are mixed with hideous suburban developments and a no man’s land of rubbish, ashes, and the skeletons of dead automobiles.” Other reporters were more favorable. Queens has been touted as an up-and-coming neighborhood for much longer than many people realize. In 1935, in an article entitled “Astoria Waterfront has possibilities,” a writer predicted that apartment buildings like those on Manhattan’s Upper East Side would soon rise in Astoria because the views from Queens were better than those from across the river.

Astoria continued to capture people’s imagination. Decades before the Lonely Planet guide named Queens as a top travel destination, intrepid reporters were touring Queens, and coming back with conflicting reports. In 1931, Robert Littel, a columnist at the New York World, wrote an unfavorable review of Astoria. Queens residents have always been proud of their neighborhood. Little received a barrage of angry letters after he called the neighborhood a place “where natural beauties and the grandeur of desolation are mixed with hideous suburban developments and a no man’s land of rubbish, ashes, and the skeletons of dead automobiles.” Other reporters were more favorable. Queens has been touted as an up-and-coming neighborhood for much longer than many people realize. In 1935, in an article entitled “Astoria Waterfront has possibilities,” a writer predicted that apartment buildings like those on Manhattan’s Upper East Side would soon rise in Astoria because the views from Queens were better than those from across the river.

After World War II, Old Astoria saw a huge influx in residents and a growth in residential construction. In the 1960s, thousands of Greek immigrants settled in the area, raising the Greek population to over 22,000 by 1980. Since the 80s, Astoria has become home to a variety of nationalities, welcoming immigrants from Egypt, Morocco, Albania, Brazil, and many other nations around the world. The 2010 Census counted 27,814 people in the tracts representing Old Astoria Village. Recent years have seen an increase in immigrants from Mexico, India, Bangladesh, and Ecuador, as well as a notable rise in the percentage of one- and two-person households without children.

THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY: TODAY AND TOMORROW

So far, the twenty-first century has been a period of tremendous change and renewed promise in Astoria. While many residential developments are planned and underway, residents have increasingly sought more access to the waterfront. The Long Island City Community Boathouse operates public paddling programs in Hallets Cove, where the neighborhood’s first European settlers once docked their boats. Green Shores NYC and the Trust for Public Land worked with the community to develop a plan for a more connected and user-friendly waterfront. And, in 2017, ferry service will return to Astoria, allowing residents to commute to Manhattan by boat for the first time in more than seventy years.

Sources:

George Armbuster Photographs, Queens Library Archives

Burrows, Edwin G and Wallace, Mike. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Eisenstadt, Peter. Encyclopedia of New York State. Syracuse University Press, 2005.

Irving, Washington. Tales of a Traveler: .The Adventures of Sam, The Black Fisherman. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1895.

Jackson, Kenneth T. The Encyclopedia of New York City. New York: Yale University Press, 1995.

Littel, Robert. Editorial. New York World, February, 1931.

Long Island Daily Press. “Astoria Waterfront Has Possibilities.” September, 1935.

Long Island Democrat “Three Historical Houses”. June, 1948.

Long Island Star Journal. “First Manhattan Mixed Here.” August, 1939.

New York City Department of City Planning, Astoria Cove Development Final Environmental Impact Statement

“Blowing Up Flood Rock.” New York Times, October, 1885.

Perkins, Sid. “When Horses Really Walked on Walked on Water.” The Chronicle of the Horse, May, 1999.

Pritchard, Evan T. Native New Yorkers: The Legacy of the Algonquin Peoples of New York. Council Oak Books, 2007.

Reier, Sharon. The Bridges of New York. Dover Publications, 2000.‘

Joseph Sandor Photographs, Queens Library Archives.

Queens Tribune. Bicentennial Supplement. July, 1976.

United States Army Corp of Engineers The Conquest of Hellgate. https://www.nan.usace.army.mil

“Papers borrowed from James Hallett and once in possession of his great ancestor William Hallett 1654-1684” Queens Library Archives Box 18 Volume 2

http://queenswestvillager.com/about/detail/history_of_long_island_city

http://www.pefagan.com/gen/queens/qmp_hal1840.htm

http://digitalarchives.queenslibrary.org/vital/access/services/Download/aql:49/SOURCE1?view=true

https://www.nan.usace.army.mil/Portals/37/docs/history/hellgate.pdf

https://www.thirteen.org/queens/history3.html

https://www.nyc.gov/html/dot/html/infrastructure/queensboro-bridge.shtml

https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/astoria-park/highlights/12547

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Pastorius

https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/astoria-park/history

Stephen A. Halsey photo: https://researchnychistory.wordpress.com/2015/05/30/stephen-alling-halsey/